1.0 Introduction

This document is based on research being undertaken on the potential to use a floor energy harvesting system within a proposed site at 32 to 34 Hill Street, Birmingham. The leading manufacturer and supplier for kinetic energy floor harvesting systems is a company named Pavegen. The product works via a foot tile that decreases by 5mm when stepped on. When the tile reduces in height it is connected to a dynamo component which allows energy to be generated used for electricity, and more commonly, lighting. Within this document the product itself and various information will be critiqued to establish findings on whether specific text stated, are true or false.

The three chosen extracts of information to critique within this document are the following:

- The Engineer – Laurence Kemball-Cook On Footstep Power

- CNET –Human energy harvesting—a very silly idea

- Modelling piezoelectric energy harvesting potential in an educational building (An Investigation into Energy Generating Tiles –Pavegen)

All other information used to produce this document can be found within the bibliography

2.0 Objectives and Considerations

The objectives chosen to research within this document are as follows:

- Costs of products, including maintenance and installation fees

- Potential energy that can be produced

- Environmental impact of the products

Individuals opinions are considered, however the quality and evidence of all information is justified. Positives and Negatives of extracts are stated and evaluated.

3.0 Costs

It is vital to understand the costs behind floor energy harvesting systems. As with any investment, costs need to be considered along with additional fees such as installation, maintenance, and disposal fees. Laurence Kemball-Cook, the founder of Pavegen, believes that in the future the product will be at the same price as an average floor tile today[1] (Harris, 2011). However this is a verbal opinion given with no evidence provided that this is possible. New materials are mentioned, but not specifically, suggesting that materials will be tested to see if improvements can be made to the product. This cannot be justified to prove whether something is true, as tested results of new materials are not given. Although the worth of eco-efficiency may be a true statement, this is a rough figure, and investments may not occur. It is also important to consider that this is stated from the founder of Pavegen, and some individuals may make assumptions of this statement being biased.

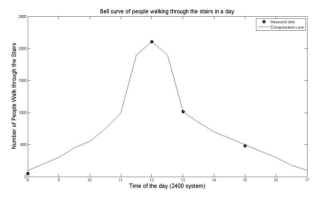

The graph below is a bell curve extracted from (An Investigation into Energy Generating Tiles –Pavegen) which is a document produced by students to es

tablish whether Pavegen tiles would be feasible to install on a staircase to the students union building of their university, The University of British Columbia. The graph shows how many people walked up and down the staircase during the day. By collecting this data, the amount of potential energy that could be produced was calculated (Seow, 2011).

Once this data had been collected and plotted, a potential payback period was generated assuming that eight Pavegen tiles would cost approximately $30,800 (Seow, 2011).

There are various parts of this test that could jeopardise the results. The bell curve chart was produced on one day, the specific day and date was not specified. The amount of pedestrians using the staircase would change on different days, and more so on weekends. As well as this the results were found by multiplying the data by 5 for a normal week, and then multiplied by 4 for a month, then finally 12 for a year. This result gave 147700 steps. This information does not account for leap years, and more importantly the student’s union building would have a far less footfall count when the university is out of term time where less students will be in the area and accessing the building. The step count is then multiplied by two on the assumption that each passer-by will step on at least two of Pavegen’s tiles. This is just an assumption and cannot justify that all pedestrians will take the same route on the staircase. Lastly the pricing of the product, stated to be approximately $30,800 for 8 tiles, is not the current pricing for the product. The document was published in 2011 and this does not allow for reduced costs by the company, inflation, and VAT changes. As well as this, the currency difference and shipping costs would result in a change in price. Pavegen are reluctant to comment on current pricing due to figures changing rapidly however, Laurence Kemball-Cook stated that pricing has dropped by around 70% since 2011, and said that each tile could be at just $50 in the near future, although there is no evidence that can support this reduction in the future (K., 2012)

Maintenance and Installation fees unfortunately are not stated with any related documents, and this information would seem only attainable through requesting quotes for specific projects through the suppliers, Pavegen, Sustainable Dance Floor, and PowerLEAP.

4.0 Energy

The amount of energy that Pavegen tiles produce is difficult to determine due to all locations having a different amount of footfall where the tiles have been installed. Pavegen claims that one of their tiles can produce around 7 watts per footstep (K., 2012). This is considerably higher than the 0.294 watts per hour that (An Investigation into Energy Generating Tiles –Pavegen) stated from their results. This could be due to the inaccuracies mentioned in section 3.0, as well as the product improving over time, allowing the tile to produce more watts per footstep. One of the company’s recent promotional projects is the Paris marathon in 2013[2]. 4.7KWh was produced on the day, however this is an unusual example as members of the marathon would be running, therefore exerting higher pressures on the tiles which could potentially create more energy than the average walking footstep. As well as this, 100’s of runners participated in the marathon which allows the tiles to host vast amounts of footsteps in a short period of time.

Another matter that needs to be considered is “Who gets to claim the energy harvested?” (Hilario, 2011). The author, Alvin Jay Hilario, elaborates on who claims human harvested energy. This would depend on the location, building use and users. For the proposed site at 32 to 34 Hill Street, Birmingham, the private office will be able to claim the energy produced off staff to power lighting within the building. However staff may need to be made aware within contracts to avoid human rights infringement. As well as this if Pavegen tiles were intended to be placed externally on the path surrounding the site, signs will need to be in place to explain to members of the public what the tiles purposes are, and the exact location of the tiles will need to be considered so that if chosen to, the public would not have to step on the tiles.

Another aspect that could be considered, which no found articles or documents have noted on, are transformers. Transformers are used to increase or decrease amounts of volts, either to supply towns and villages, or small transformers that will increase and decrease volts for a powered appliance (Britannica, n.d.). Although Pavegen and competitors may have given this some thought, small transformers could be used to increase the amount of energy produced each footstep, therefore allowing the product to be more energy efficient.

5.0 Environmental Impact

Being a sustainable product, creating clean energy, the system is interpreted to be beneficial to the environment. However the environmental impact needs to be looked into further to see how environmentally clean the product really is.

Pavegen claims that the majority of its product is made from recycled materials.[3] This results in the mechanism being looked upon as having very little environmental impact. However within research taken from (An Investigation into Energy Generating Tiles –Pavegen) the shipping of the product can change the environmental impact vastly due to the carbon dioxide produced.

The manufacturing process also needs to be considered. Even though Laurence Kemball-Cook states that the majority of the product is made from recycled materials, the actual manufacturing process of the tiles will produce an amount of carbon dioxide. Although the percentage produced cannot be determined, this needs to be considered.

6.0 Case Studies

The leading floor energy harvesting system manufacturer, who has been referenced throughout this document, is Pavegen. The company now has a portfolio of over 100 projects, however the majority of these have been promotional and for companies that have invested in Pavegen. The first commercial order for the product was for Westfield Stratford City Shopping Centre in London (Brown, 2011).

A good case study to consider is Renaissance Capital Partners Ltd. This is the first project that Pavegen have installed their product into a contemporary commercial office. The particular project will relate to the proposed construction at 32 to 34 Hill St, Birmingham.

7.0 Conclusion

Although being a relatively new and a specific product within the renewable energy market, all relevant information has been interpreted and justified to review floor energy harvesting systems. On first thought the assumptions were made on the product being innovative, and energy efficient. After researching various information on costs, it shows that the product has reduced in price, and hopes to continue further reductions. Not long ago the system would appear to not be very beneficial to a client as the payback period would be too long, however within section 3.0 of this document it proves this information could be false. With the founder of Pavegen stating that there will be further reductions for clients wanting to purchase the product, although this would seem believable, there is no physical evidence that can be located to support this.

The environmental impact would initially be assumed as very low. However after researching the manufacturing process of the product, no information could be found. This could suggest that Pavegen and competitors wish not to state how the tiles are produced to hide how much carbon dioxide is potentially produced and to leave the public unaware of the negative impact it could have on the environment. Shipping is also an issue with suppliers. Projects that have been completed abroad in distant locations such as the United States would have caused a negative impact on the environment due to the amount of carbon dioxide produced having to ship the product from London, United Kingdom. However Pavegen have recently opened Pavegen Korea within South Korea (Pavegen, Pavegen Korea Launched, 2015) which proves the company is continuing to grow and will perhaps branch out to further locations within the future which will help supply clients on a more local basis, therefore reducing the negative impact on the environment due to the reduction of shipping. This could also reduce costs for clients purchasing the product.

Competitors of Pavegen have been considered and researched through the production of this document, however they have not been considered highly due to Pavegen being the market leader within the floor energy harvesting sector. Competitor companies are energy floors, based in the Netherlands and PowerLEAP in Michigan, United States. However these companies are not as popular as Pavegen due to not receiving as much investment and incorporating as much advertisement on their products. As well as this Laurence Kemball-Cook states that Pavegen’s tiles are 200 times more efficient at producing power than any rival product (K., 2012). Although this cannot be proven due to a lack of evidence and data that could support the statement.

Discussions and investigations that may arise from this document could be the following:

- Will the costs of the products reduce significantly through Pavegen’s and other competitor’s growth?

- Through further growth, will Pavegen and competitors be able to branch out to further locations, therefore reducing the environmental impact through unrequired shipping?

- How much impact on the environment does the manufacturing process have on floor energy harvesting systems?

- Will products be able to be developed further to produce more energy? Either by increasing the watts produced per footstep, or being able to multiply the energy produced by a transformer?

- Are floor energy harvesting systems an invasion of human rights?

The author of this document believes that discussions and research will be aided through utilised information stated within the articles provided, and that considerations will be made in breadth when interpreting data and statements.

8.0. Bibliography

Literature:

Britannica, E. (n.d.). http://www.britannica.com/technology/transformer-electronics. Retrieved 11 23, 2015, from http://www.britannica.com/.

Brown, M. (2011, 09 30). http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2011-09/30/pavegen-in-london-shopping-centre. Retrieved 11 24, 2015, from http://www.wired.co.uk/.

Davies, G. H. (2014). http://www.garethhuwdavies.com/environment/green_tech/pavegens-energy-from-footsteps-advance-faster-than-solar/. Retrieved 11 24, 2015, from http://www.garethhuwdavies.com/.

Ellis, V. (2012, 11 07). http://www.energylivenews.com/2012/07/11/foot-power-lights-up-olympic-walkway/. Retrieved 11 22, 2015, from http://www.energylivenews.com/.

Glaskowsky, P. (2007). Human energy harvesting–a very silly idea. Human energy harvesting–a very silly idea, 0-2. Retrieved 11 03, 2015

Gregory, M. (2013, 07 16). http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-23281950. Retrieved 10 29, 2015, from http://www.bbc.co.uk.

- S. Lohit, C. D. (2014, 04). http://www.msruas.ac.in/pdf_files/sastechJournals/April2014/10.pdf. Retrieved 11 20, 2015, from http://www.msruas.ac.in.

Harris, S. (2011, 11 14). http://www.theengineer.co.uk/in-depth/interviews/pavegen-founder-laurence-kemballcook/1010877.article. Retrieved 11 03, 2015, from theengineer.co.uk.

Hilario, A. J. (2011, 05). Energy Harvesting From Elliptical Machines Using Four-Switch Buck-Boost Topology. Page 18 out 130.

ISRI. (2007). Carbon Footprint OF USE Rubber Tire Recycling. Carbon Footprint OF USE Rubber Tire Recycling, 0-13. Retrieved 11 02, 2015

K., T. (2012, 05 20). http://www.nationalgeographic.com/. Retrieved 11 22, 2015, from http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/energy/2012/05/120518-floor-tiles-turn-footfalls-to-electricity/.

Marrero, L. (2015). Gensler Vision for Disused London Metro Lines Wins London Planning Award. Concept would offer London the first network of subterranean pedestrian and bike paths, powered by energy-generating Pavegen tiles., 0-1. Retrieved 03 22, 2015

Mayors, E. (2015). The Emission Factors. Technical annex to the SEAP template, 0-4. Retrieved 11 02, 2015

Pavegen. (2012, 10 03). Fig. 1. Pavegen powers Olympics transport hub from footsteps. Retrieved 11 02, 2015

Pavegen. (2015). http://pavegen.com/about. Retrieved 10 28, 2015, from http://pavegen.com.

Pavegen. (2015, 09). Pavegen Korea Launched. Retrieved 11 23, 2015, from http://pavegen.com/blog/pavegen-korea-launched-help-apple-founder.

Pavegen. (n.d.). Installation Manual. Product Specification Pavegen Mark 1.8, 0-22. Retrieved 10 30, 2015

Pavegen. (n.d.). Installation Manual – Raised Floor. Permanent Raised-Floor Installation. Retrieved 10 30, 2015

Petroleum, B. (2014). BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2014. 0-48. Retrieved 11 01, 2015

Portfolio, P. (2015). http://pavegen.com/projects. Retrieved 10 30, 2015, from http://www.pavegen.com.

Seow, Z. L. (2011, 11 24). https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/undergraduateresearch/18861/items/1.0108425. Retrieved 11 14, 2015, from http://www.library.ubc.ca/.

Webster, G. (2011, October 13). http://edition.cnn.com/2011/10/13/tech/innovation/pavegen-kinetic-pavements/. Retrieved 10 29, 2015, from editioncnn.com.

Xiaofeng Li, V. S. (2014). Modelling piezoeletric energy harvesting potential in an educational building. Energy Conversion and Management, 0-8. Retrieved 10 31, 2015

Images:

Figure 2: (Seow, 2011)

[1] ’Eco-efficiency will be worth about $4bn [£2.6bn] by 2021 so there’s going to be significant investment in the industry. As we commercialise it and use new materials we anticipate our unit cost dropping substantially to a point where it’s on par with the cost of a normal paving slab.’

[2] “Pavegen laid 176 tiles at the Paris Marathon, spanning the finish line at the Champs-Elysées. Runners and the crowd generated 4.7 kWh”.

[3] It’s all made from recycled materials (recycled aluminium for the internal components and the steps are made with rubber from old tires).